Winslow Homer's Painting Class

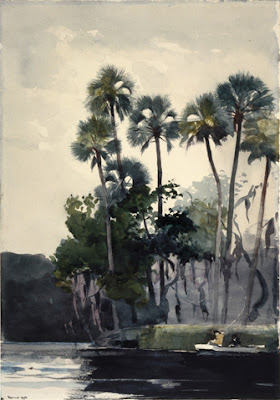

Here's a watercolor by Winslow Homer (Homosassa River, 1904 from the Brooklyn Museum) that caught my eye the other day. Realize it's done with an extremely restricted palette (except for a tiny red jacket on one of the fishermen, it's got hardly any intense color in it). Homer's bringing this one home with his remarkable ability to improvise and to "lie" about what he was looking at. How did he learn how to do this so well?

It got me to wondering what sort of painting class Winslow Homer would run if he were to come back to life and hire a model.

Here is part of my figure painting workshop Dec. 10 at the Saginaw Art Museum. Kara Harris Brown, the Museum's Curator of Education did a great job of organizing the event (including bringing lots of donuts). I think everyone enjoyed themselves. I know I did.

Watching my students work, it struck me the more accomplished painters had learned not just about color and composition. but also how to have a good time. Beginning painters seemed hell bent on concentrating on the model. Of course one wants to master the figure, but it's possible to overdo anything. The more experienced of course had better drawing skills and a certain confidence that allowed them to relax more. Most important, they were quicker to notice things others might miss and see if they might make something surprising but convincingly expressive out of them. For example, the unexpected shape of the space between the model's legs and finding a way to make that one of the key features of the painting.

Looking at a detail of the Winslow Homer watercolor, you see how he "plays" with the background, making it dark at the far left, but leaving it only a light middle tone on the right hand half of the painting.

He did this I believe to allow those early wild looking strokes for the straight and curved tree trunks to keep from being lost in the darks. Probably in real life, the far distance was much darker, but Homer is willing to make big changes if he senses it will leave him a more intriguing composition.

Here's my favorite part of the picture, the fan-shaped holes in the palm fronds. Don't they look like eyes!

Their empty centers are left as the key accents in the top half of the painting. Look at how in comparison he tones down the branches and lightens up much of the main trunks to lighter greys. To me it seems Homer is saying to himself "let's see what I can do with this row of trees." He's not imprisoned with the mindset that he has to report to us every fact faithfully. Look back up to the entire painting at the top of the post- see how much Homer left out. This is the nuts and bolts of him being creative for us viewers.

Charles Burchfield, the American 20th century painter, and one of our supreme watercolorists, must have looked at Homer a lot. In the Burchfield below notice the same decorative repeated patterns in the foliage. Both of these artists are playfully seeing what they can do with the material presented them by their subject. Both of them know painting is at least as much about how they paint something as what it is they choose to paint.

In Winslow Homer's imaginary painting class I'm sure he'd be a serious stickler for making his students become superbly good at drawing what they see. Imagine all sorts of stern 19th century style pedagogical excess. But he wouldn't stop there. He'd also insist his students be playful, that they imagine how things in their source might be moved around, have their color changed, or perhaps be eliminated altogether. He'd demand of his students that they go beyond mere reporting of facts to exaggerate their favorite ideas, pushing their ideas beyond what one would normally expect. He'd insist on his students finding delight in what their eyes could show them.

Would we want anything less from his students? I wonder where I can sign up for his class.