Major Landscape Exhibition at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts / Part One

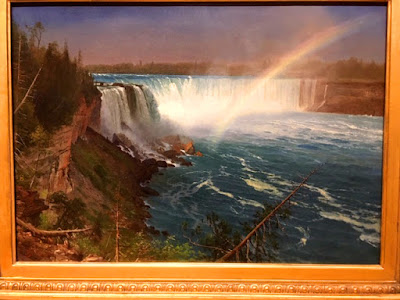

Albert Bierstadt, Niagara, oil on paper laid down

on canvas, 1869

One of the things that sustains me as a landscape painter is understanding I am part of an historic movement of artists who took delight in our planet. Each generation of landscape painters adds their own contemporary voice to a chain of paintings stretching back hundreds of years. Especially in our time of impending climate crisis reigniting the deep strain of environmental sentiment that runs all through American landscape art is part of my personal mission.

This week Anna Marley, the Curator of Historic American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, very kindly gave me and my wife a personal tour of her major exhibition From the Schuylkill to the Hudson: Landscapes of the Early American Republic shining a light on the earlier beginnings of landscape painting our country. Contrary to the usual understanding, Marley shows the much better known artists of the New York based Hudson River School owe their beginnings to painters who stoked the fires of landscape art in Philadelphia,

My wife Alice in the Pennsylvania Academy's historic

building next door to the Schuylkill exhibition. It's one

of the most beautiful buildings I've ever seen. Plus the

Academy's permanent collection is to die for.

I got a particular "Aha!" moment from the exhibition. Until my fourth birthday we lived in the town of Fairport, NY just two blocks from the old Erie Canal. At that age all I remember was watching the lift bridge over the Canal go up was the greatest thing in the world. What I only now put together was the impact the1825 opening of the Canal had on America. Prior to that Philadelphia was our big city and our cultural capital. The Academy was our first art museum and to this day is our oldest art school (I teach at the 2nd oldest, MICA in Baltimore).

The Canal connected the New York City to the Great Lakes, opening a surge in shipping that propelled the the city to rapidly outstrip Philadelphia as a commercial center. For artists it also meant that's where new patrons were to be found.

Exhibition signage greeting visitors

My wife Alice with the giant exhibition map

displaying the wide ranging locations where the painters

in the exhibition found their subjects.

Marley takes note of the important reality that the banks of the Schuylkill River had been inhabited for centuries before the arrival of European colonist by the Lenape peoples.

Artists always have to begin somewhere. Some of the earliest paintings in the exhibition are by artists originally trained as military draughtsmen. Required to accurately record the topographical facts of a given terrain, they often leaned toward insistently describing objects in the foreground of their paintings (see the Thomas Birch oil below).

Another key influence was the tradition of landscape as a backdrop in formal portraiture where the wealthy subjects were portrayed standing outdoors surveying the grounds of their estate. Theres a key example early in the exhibition of this by Charles Willson Peale.

The Academy recently acquired what may be the earliest known painting of the Schuylkill by the British born immigrant George Beck. It relies heavily on Baroque and 18th century conventions of European landscape painting. It's got a great rhythm to it.

George Beck, Schuylkill Below the Falls,

watercolor, circa 1798

Thomas Cole, whose work would in a few years burst forth and inspire the artists of what came to be the Hudson River School studied in the early 1820's at the Pennsylvania Academy. Anna Marley told me Cole drew from the schools plaster casts of classical sculpture, studied the paintings in the museum's collection, and participated in annual exhibitions of the Academy. The painters Thomas Birch and Thomas Doughty, both associated with the Academy, were particular influences on Cole.

The young Cole confessed to feeling intimidated by works like this Schylkill view by Birch of the just constructed waterworks that damed the river and provided fresh water to the city. Though in only a few years Cole's talent would flower in ways that to me far surpass Thomas Birch, Cole remarked to an early art historian that "his heart sunk as he felt his deficiencies in art when standing before the landscapes of Birch." As a painter I find that confession refreshing. It confirms my feeling that the most talented of artists always have a quiet battle going on between their confidence and their questioning each decision as they paint.

Thomas Birch, The Fairmount Water Works, oil

on canvas, 1821

This Thomas Doughty in the show seems so much closer to the romantic spirit of the sublime that Thomas Cole would later often adopt. It think it's a terrific painting with enviable geometric shapes in the sky and masses of trees wrapping the whole composition together.

Thomas Doughty, Land Storm, oil on canvas

1822

As the show points out the artists over time began to branch out from the confines of just the Schuylkill and the Hudson. Here's a sensitive atmospheric piece from Thomas Cole's later travels in Italy.

Thomas Cole, View of Sicily, oil on wood panel,

1842-45

The Erie Canal made it a lot easier for artists to get to the great natural wonder of Niagara Falls and it became a favored subject. There's a fun projected video in the middle of the galleries of a cascading waterfall. Here's some of the young participants in the Museum's summer camp checking out the spray.

Marley also notes the way women were relegated to a very secondary role in the art world of the time.

Fenner, Sears & Co., after Thomas Cole's

painting A Distant View of the Falls of Niagara,

etching and engraving, 1831

painting A Distant View of the Falls of Niagara,

etching and engraving, 1831

Highly popular at the time were ceramics decorated with landscape imagery. Marley explained many of the workers employed in this were women. Below is an example of a design borrowed from Cole's Niagara on a platter.

William Adams and Sons Factory after Thomas

Cole's painting The Falls of the Niagara, earthenware

and lead glaze platter

In a second blog post I want to show later work from the exhibition. In many ways I feel it is the most accomplished. But it was only possible because these later painters had the shoulders of their predecessor artists to stand on. Here below I'm posing with Anna Marley in from of my favorite piece in the exhibition, the stunning Valley of Santa Isabel, New Granada by Thomas Cole's student Frederic Church from 1875. It's a new acquisition by the Academy.